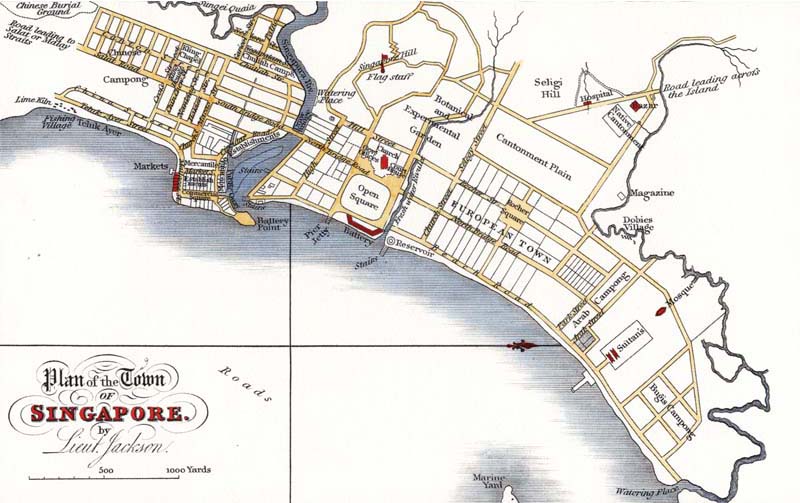

Plan of the Town of Singapore, 1823, by Lt. Philip Jackson, which is also known as the Raffles Town Plan. Jackson, L. (1822). Plan of the town of Singapore. London: J & C Walker.

Since Independence, Singapore has witnessed many dramatic changes to its urban landscape. The overcrowded city centre of the 1960s characterised by slums, filthy drains, congested roads and ageing infrastructure has been replaced by a modern business and financial hub. The streets are safe and clean, and lined with buildings that provide a vibrant mix of retail and entertainment activities. Beyond the city limits lies an impressive network of self-sufficient towns. Not only do these towns provide good quality homes and ample recreational space for residents, they are also connected to the city and each other by an efficient transportation system.

The changes to Singapore’s urban landscape have been shaped by a land use strategy that has been evolving for the past five decades in tandem with the nation’s changing needs. These changes have been systematic and implemented under the guidance of the Concept Plan – the country’s strategic land use and transportation plan. By examining Singapore’s previous concept plans as well as their objectives and directions, this article will assess the impact of this planning instrument in transforming the country’s physical landscape.

Land use planning in Singapore is not a recent concept. In fact, the first town plan of Singapore was drawn up by surveyor Lieutenant Philip Jackson in 1823. Widely referred to as the Raffles Town Plan, it was based on instructions by Stamford Raffles to the town committee in November 1822. 1 The aim of the town plan was to ensure “an economical and proper allotment of the ground intended to form the site of the principal town”. 2 To this end, the plan parcelled the proposed town area, located within a 2- to 3-kilometre radius from the Singapore River, into distinctive districts for the seat of government, merchants and each of the major ethnic communities, namely the Chinese, Malays, Indians and Europeans. 3

The Raffles Town Plan largely dictated the physical development of the city centre until the 1870s. However, the effectiveness of the colonial plan began to erode as it succumbed to the pressure of the settlement’s ballooning population – 10,683 in 1834 to 137,722 by the end of 1881. 4 In the absence of an updated town plan and proper controls, the city centre was described in the press as a “pig sty” by the turn of the century. 5 It was severely overcrowded, disorganised and polluted, compounded by huge pockets of slums and hampered by congested roads. 6

As the population explosion continued throughout the pre-war and immediate post-war years – almost reaching 1 million by the end of 1947 – it became clear to the colonial government that something had to be done to address the deteriorating living conditions in the city. 7 The Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) was set up in 1927 to alleviate the overcrowding and housing problems in the city area by building low- to medium-rise flats, but the attempt met with little success. 8 The lack of housing fuelled the growth of the squatter population that rose to about 150,000 (15 percent of the total population) in 1953. 9 To prevent the problem from escalating further, the colonial government decided to re-introduce the idea of a planned environment to regulate the physical development of the city centre. 10

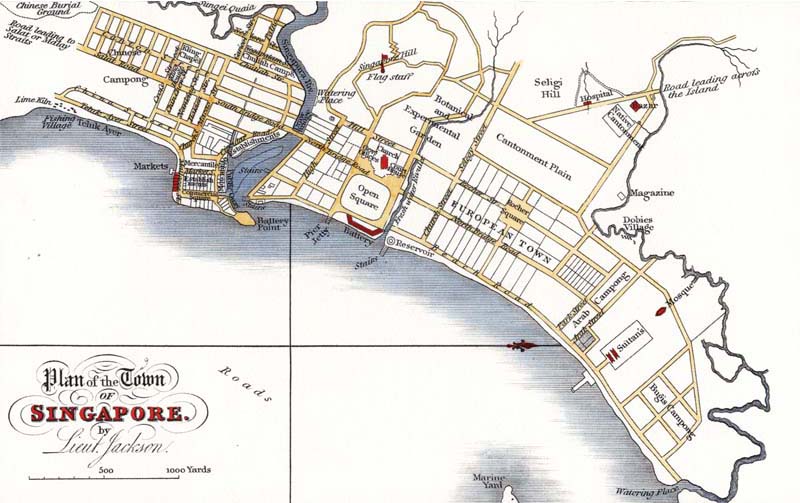

In 1951, following an amendment to the Singapore Improvement Ordinance, the SIT was tasked with conducting an island-wide survey of Singapore to prepare a master plan to guide its physical growth for the next 20 years. 11 The statutory master plan, completed in 1955 and approved in 1958, was Singapore’s first long-term land use plan since the Raffles Town Plan. 12 Using survey data on population, land use, traffic, employment and industrial development, the 1958 Master Plan provided a general framework for the orderly physical development of Singapore and the optimal use of land. 13 It set regulations for land use through zoning and controlled the intensity of development on land sites through density for residential use and plot ratio for non-residential use. 14

The Master Plan also catered land for schools, infrastructural facilities and recreational use, including a green belt to limit the expansion of the city. 15 Most importantly, it accounted for the creation of new satellite towns such as Woodlands, Bulim (now a sub-zone of Jurong West) and Yio Chu Kang that were located away from the city centre. 16 This concept was an idea borrowed from the Greater London Plan of 1944 and sought to tackle the acute overcrowding and housing problems by moving people away from the city centre to outlying areas. 17

Despite the comprehensive planning, the 1958 Master Plan was fundamentally a static concept, providing for limited and predictable change and for a city of finite size. 18 The land use changes it proposed were based on the assumption that urban growth would be slow and steady, premised on a projected population of 2 million by 1972. 19 The plan also assumed that the private rather than public sector would lead the physical development of the city after Singapore achieved full internal self-government in 1959. 20 With such a rigid and limited scope, the 1958 Master Plan was unable to respond to the country’s land use pattern which changed dramatically after the newly elected People’s Action Party (PAP) government introduced a series of large-scale housing and industrial projects. 21 Recognising the ineffectiveness of the Master Plan, the government decided to review the plan’s planning strategies with the intention of replacing them with a more responsive instrument to facilitate long-term planning in land use. 22

Map 2: 1958 Master Plan © Urban Redevelopment Authority. All rights reserved.

To find a new approach, the government sought the help of the United Nations (UN), which sent two teams in 1962 and 1963 respectively to review the effectiveness of the 1958 Master Plan. Both teams agreed that the 1958 plan was conceptually too conservative and recommended that it should be replaced, and that the process of planning be institutionalised and coordinated in action programmes for greater efficiency. 23 The culmination of the UN review process was the launch of the State and City Planning (SCP) project to prepare for a new long-range comprehensive land use plan to guide the physical development of the country. The resulting plan, which was one of the 13 “ideas” plans produced subsequently, would later be unveiled in 1971 as the first Concept Plan of Singapore. 24

Unlike the 1958 Master Plan, the Concept Plan is a strategic long-range land use and transportation plan that provides broad directions to guide Singapore’s physical development. It expresses the government’s long-term planning intentions for the nation’s territory as a whole. 25 To ensure the directions set in the Concept Plan are relevant and responsive to the changing needs of the nation, it was agreed that the non-statutory document would be reviewed every 10 years. 26 The preparation of the Concept Plan was a collective effort that involved other government agencies as well as the public so that the planning would take all major land use demands – such as housing, industry and commerce, recreation and nature areas, transport and utility infrastructure – into consideration. 27

In retrospect, the Concept Plan was vastly different from the planning approach of the Master Plan as the latter only concentrated on sectoral needs, particularly housing. 28 From the very beginning, the SCP project was made up of a number of departments – with the Planning Department as its nucleus, comprising staff from the Urban Renewal Department, the Housing and Development Board and the Public Works Department. In addition, the SCP team worked closely with the United Nations Development Programme, bringing in planning practices and expertise that were conducive to the drafting of the first Concept Plan. 29

Interestingly, the injection of the Concept Plan into Singapore’s land planning strategy has not rendered the Master Plan irrelevant. As the Concept Plan is a planning instrument that provides the backdrop for the preparation of the Master Plan, the latter remains an integral stage in overall land planning. The Master Plan functions as the statutory tool that guides the physical development of Singapore by translating the broad long-term strategies of the Concept Plan into detailed plans showing the permissible land use and development density for every parcel of land. 30 To ensure that the planning principles in the Master Plan do not stay static, it is reviewed every five years. 31

Based on the planning directions set out in the Concept Plan and Master Plan, land for development is then released through the Government Land Sales (GLS) programme. Singapore’s built heritage is not forgotten in this strategy as conservation plans are also drawn up to preserve the city’s overall urban design. 32 All these different stages of planning and implementation ensure that the country’s limited land resources are optimised to the fullest and the urban environment made attractive. 33

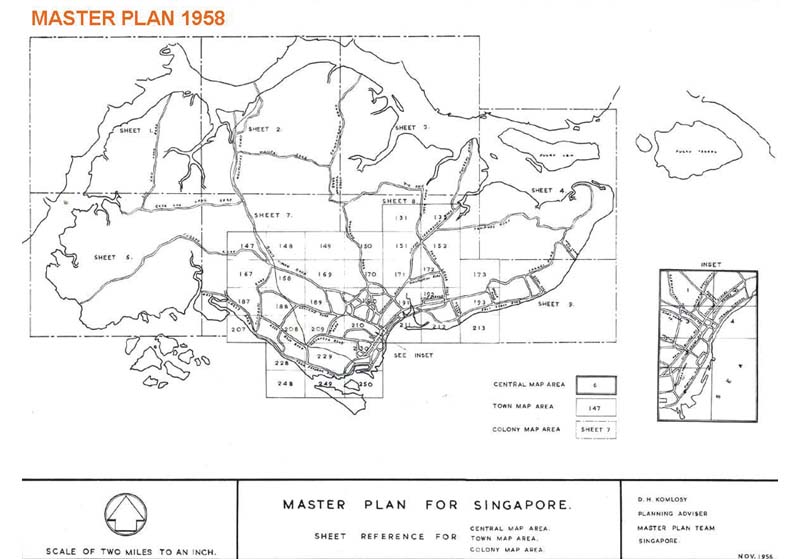

The Concept Plan has been revised several times since its introduction in 1971. In each revision, an overall strategy was adopted to ensure that the country’s land use plans met the changing needs of the nation. New features were added based on these strategies, which in turn had a profound effect on Singapore’s physical landscape. For instance, the 1971 Concept Plan was drafted with the infrastructure needs of a new nation in mind. As such, the plan was instrumental in laying the foundation of Singapore’s transportation infrastructure. 34 Key transport developments such as Changi Airport, the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) system and the island-wide network of expressways were the outcomes of strategies outlined in the 1971 Concept Plan. 35 Apart from serving the needs of an industrialised economy, these developments also facilitated the “Ring Plan” structure. 36

1971 Concept Plan © Urban Redevelopment Authority. All rights reserved.

The Ring Plan was the 1971 Concept Plan’s strategy to move the population, projected to hit 4 million by 1991, out of the overcrowded central area to outlying satellite towns. This is similar to the satellite town concept proposed in the 1958 Master Plan, albeit on a grander scale. The Ring Plan is a ring of high-density satellite residential towns encircling the central water catchment area. 37 Populated with mostly medium-density and high-density public housing, the plan was for the towns to be linked to each other as well as to the Jurong Industrial Estate and the city area by the MRT and expressways. At the same time, the satellite towns were to be separated from each other by a system of parks and green spaces – another key feature of Singapore’s present landscape. 38 The central area was designed to be a strong financial business district to attract foreign capital as well as local investments and expedite Singapore’s industrialisation programme. 39

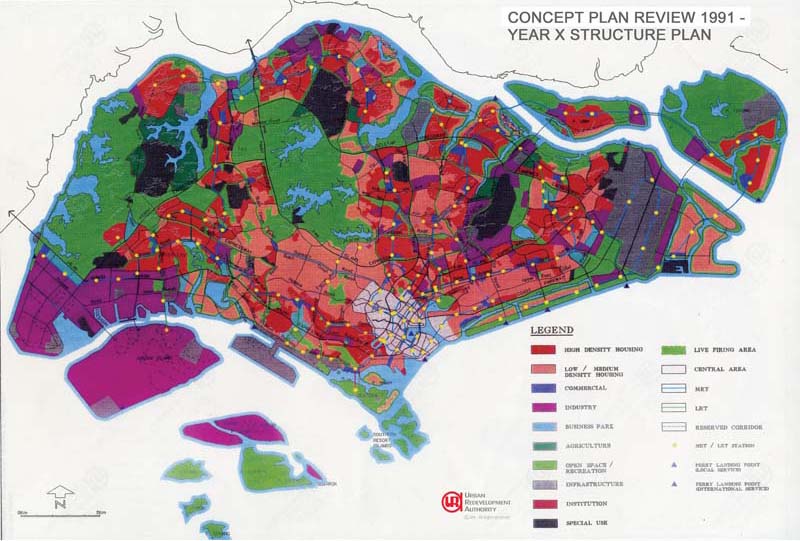

The 1971 Concept Plan was subsequently reviewed and replaced by the 1991 Concept Plan. The new Concept Plan came at a very different period in Singapore’s history; by this time many problems linked with the colonial era, such as housing and unemployment, had been effectively ironed out. Moreover, the country was on the verge of reaching developed status with one of the strongest economies and highest GDP per capita in Asia. 40 With this change in socioeconomic status, the vision of the 1991 Concept Plan was to turn Singapore into a Tropical City of Excellence that balanced work, play, culture and commerce by Year X beyond 2010. 41

To realise this higher quality of living, the Concept Plan introduced a “Green Blue Plan”, which identified a connected network of parks, natural green spaces and waterways to create more leisure and recreational opportunities for the people. 42 It also proposed conservation efforts to safeguard Singapore’s built heritage in the city centre and measures to promote the arts and culture. 43 In fact, the museum precinct around the foot of Fort Canning, the National Library building on Victoria Street and the network of public libraries around the island are all results of the 1991 Concept Plan. 44

To meet the needs of the changing economic structure, particularly to facilitate the growth of high-technology industries, the 1991 Concept Plan called for the creation of technological corridors. Comprising business parks, science parks and academic institutions, these corridors were designed to provide researchers with integrated working, living and leisure environments. Situated near existing tertiary institutions, these corridors aim to facilitate the exchange of ideas and innovation among researchers at all levels. 45 The establishment of Science Park and OneNorth in the western part of Singapore near the National University of Singapore and Singapore Polytechnic are the outcomes of this proposal. 46 Besides technological corridors, the Concept Plan catered for other value-added industries, proposing for the amalgamation of the southern islands off Jurong to support the development of a petrochemical industry. 47 It also planned for a new downtown to be created in Marina South to expand the business district. 48

The 1991 Concept Plan also included the creation of 10 new satellite towns to accommodate a population that was projected to hit 3.23 million by 2000. It also revised the 1971 Ring Plan to a “Constellation Plan”. Based on a policy of decentralisation, this housing strategy was to “fan” the commercial centres out to the heartlands so that jobs could be brought closer to homes and alleviate congestion in the city centre. The plan called for the development of regional and sub-regional commercial centres that would be served by new expressways and MRT lines. 49 This led to the development of the Woodlands, Tampines and Jurong East regional centres respectively in the northern, eastern and western parts of Singapore as well as the introduction of the North-East MRT line and the Paya Lebar Expressway. 50

1991 Concept Plan © Urban Redevelopment Authority. All rights reserved.

The focus of the 2001 Concept Plan was to turn Singapore into a thriving world-class city in the 21st century by creating a “live-work-play environment, a dynamic city for business, leisure and entertainment”, as well as “a deep sense of identity by creating a distinctive and delightful city”. 51 Projecting the population to hit 5.5 million by 2051 – which in reality had already reached 5.39 million in 2013 due to liberal immigration policies 52 – the 2001 Concept Plan promised a wider choice of housing options and types, whether high-rise or otherwise, to meet different lifestyle needs and aspirations as well as to inject vibrancy into the central area. 53 It also proposed extending existing MRT lines by constructing an extensive rail network based on an orbital and radial concept. 54 This proposal led to the introduction of the Circle Line, Downtown Line and upcoming Thomson and Eastern Region Lines. 55

A Parks and Waterbodies Plan was introduced along with the Concept Plan, proposing initiatives such as the enlargement of existing parks, better distribution of parks throughout the island, greater access to nature areas, development of four new waterfront parks and expansion of the park connector network. The plan resulted in the Sengkang Riverside Park and Woodlands Regional Park. 56 It also led to the Southern Ridges trail, the expansion of the park connector network to over 200 kilometres and the creation of rooftop, vertical and balcony gardens to enhance the greening of buildings and streetscapes. 57

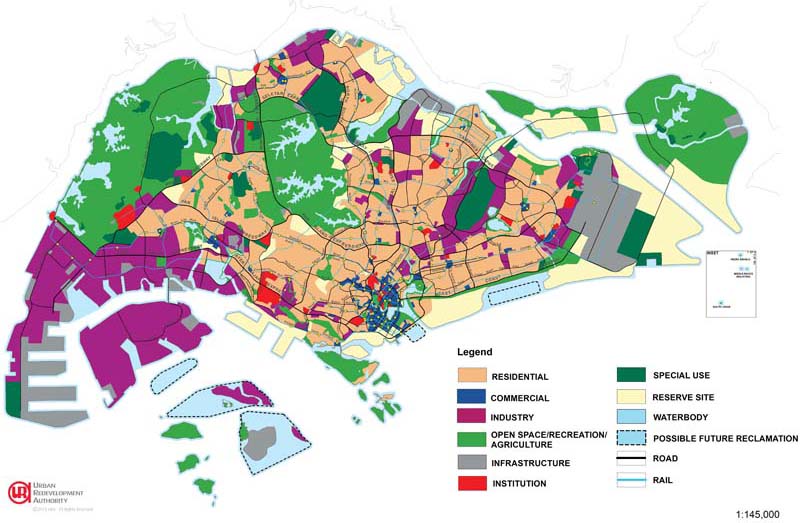

The most recent review of the Concept Plan was carried out in 2011. However, the process was extended to take into account a public feedback exercise led by the National Population & Talent Division (NPTD). 58 Findings from the Concept Plan review were later released as part of the 2013 Land Use Plan, a document by the Ministry of National Development outlining the land use strategies to provide the physical capacity to sustain a high-quality living environment for a possible population range of 6.5 to 6.9 million by 2030 (as projected in the 2013 Population White Paper, the result of the NPTD’s population discussion). 59

The key findings included: the creation of more people-centric homes; incorporation of the principles of community and inter-generational bonding in the design of public housing; better community facilities and infrastructure; expanding existing public transportation and park connector systems; strengthening the nation’s green infrastructure; and protecting the country’s built heritage. 60 These findings serve as the backdrop for a number of initiatives in the Land Use Plan. For example, the “Remaking Our Heartland” programme hopes to redevelop older estates such as East Coast, Yishun and Queenstown with more people-centric homes and multi-generational facilities, while the “City in the Garden” vision will see the creation of more parks and a 150-kilometre Round-Island-Route that will link the major built and natural heritage landmarks of Singapore. 61

2013 Land Use Plan © Urban Redevelopment Authority. All rights reserved.

It is clear that the government will continue to use the Concept Plans to express its long-term planning intentions. Through a collective consultative process with relevant government agencies and the public, the Concept Plan of the future will continue to chart the land use and infrastructure development of Singapore, create solutions to safeguard the environment, sustain the economy and improve the quality of living for future generations. The Concept Plans will also be reviewed regularly so that they can remain flexible and responsive in order to meet the changing needs of the nation.

PRESERVING HERITAGE

One of the most enduring impacts of the nation’s town planning efforts was the launch of the conservation programme in the 1980s. Prior to that, the lack of an articulated conservation plan had resulted in the demolition of many buildings with historical and architectural significance such as Bukit Rose in Bukit Timah, the OId China Building and the Old Arcade in the name of progress. 62 As noted in the 1991 Concept Plan, the aim of conservation is preserve the nation’s built heritage so that historic buildings can be used as physical landmarks that illustrate Singapore’s rich, multi-ethnic background. 63 The first shophouses to be conserved and restored were in Tanjong Pagar in 1987. Thereafter, over 7,000 heritage buildings and structures in more than 100 locations were gazetted for conservation. These buildings were selected based on their architectural significance and rarity; cultural, social, religious and historical significance; contribution to the environment and identity; and economic impact. 64

Shophouses in the Tanjong Pagar area were among the first heritage structures to be restored in 1987. MITA collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

MARINA BAY DOWNTOWN: A VISION FROM 1991

Spanning 360 hectares, Marina Bay downtown is the extension of Singapore’s central business district along Shenton Way. It is a waterfront business district similar to London’s Canary Wharf and Shanghai’s Pudong. 65 Most people think of the glittering Marina Bay area as a 21st century addition to the skyline when in actual fact the new downtown plan was first proposed in the 1991 Concept Plan, and the massive land reclamation project to create Marina Bay actually started in the 1970s. 66 Marina Bay is different from other urban areas in Singapore in that it encourages a mix of commercial, residential and entertainment activities in land usage. This is to ensure vibrancy in the area around the clock. To facilitate this, “white” site zoning was introduced to demarcate sites for mixed-use development. 67 This different planning approach is clearly reflected in the skyline of Marina Bay as its glass and steel financial buildings stand side-by-side with high-rise luxury apartments while overlooking green spaces such as Gardens by the Bay and the entertainment and dining hub of Marina Bay Sands.

The development of Marina Bay downtown was first proposed in the 1991 Concept Plan. Courtesy of Gardens by the Bay.

The development of Marina Bay downtown was first proposed in the 1991 Concept Plan. Courtesy of Gardens by the Bay.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013); Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010).

Buckley, C.B. (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BUC-[HIS])

Colony of Singapore. (1958). Master plan: Written statement. Singapore: Tien Wah Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 711.4095957 SIN) Dale, O.J. (1999). Urban planning in Singapore: Transformation of a city. Shah Alam, Malaysia: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: R 307.1216 DAL)

Ee. E. (2013). At the forefront: Leading the new downtown. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 307.34216095957 EE)

Kong, L. (2011). Conserving the past, creating the future: Urban heritage in Singapore. Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no.: RSING 363.69095957 KON)

Lall, S.V. et.al. (Eds.). (2009). Urban land markets: Improving land management for successful urbanisation. Dordrecht: London: Springer. (Not available in NLB’s holdings)

Liu, T.K., et. al. (Eds.). (2014). Liveable sustainable cities: A framework. Singapore: Civil Service College: Centre of Liveable Cities. (Call no.: RSING 307.1216095957 LIV)

Ministry of National Development. (2013). A high quality living environment for all Singaporeans: Land use plan to support Singapore’s future population. Singapore: Ministry of National Development. (Call no.: RSING 333.77095957 HIG)

Ong, K. Y., & Lee, T.Y. (2010). Final report of focus group on sustainability and identity: Concept plan review 2011. Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no.: RSING 307.76095957 SIN)

Pearson, H.F. (1969, July). Lt. Jackson’s plan of Singapore. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 42 (1) (215), pp. 161–165. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Saw, S-H. (2012). The population of Singapore. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 304.6095957 SAW)

Serene, T., & Serene, T. (Eds.). (2012). Designing our city: Planning for a sustainable Singapore. Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no.: RSING 307.1216095957 DES)

Singapore. Planning Department. (1970). Annual report 1968 & 1969. Singapore: Planning Department. (Call no.: RCLOS 711.4095957 SPDAR; Microfilm no.: NL 11783)

Singapore. Planning Department. (1975). Revised master plan: Report of survey. Singapore: Planning Department. (Not available in NLB’s holdings)

Tan, C.C., & Cheng, E. (2010). Final report of focus group on quality of life: Concept plan review 2011. Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no.: RSING 307.76095957 SIN)

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (1991). Living the next lap: Towards a tropical city of excellence. Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no.: RSING 307.36095957 LIV)

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (2001). The concept plan 2001. Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no.: RSING 337.36095957 CON)

Waller, E. (2001). Landscape planning in Singapore. Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING q307.1216095957 SPA)

Wong, T.C. et al. (Eds.). Spatial planning for a sustainable Singapore. Dordrecht: London: Springer. (Call no.: RSING 307.12160959957 SPA)

Yuen, B. (Ed.). (1998). Planning Singapore: From plan to implementation. Singapore: Singapore Institute of Planners. (Call no.: RSING 711.4095957 PLA)